Last Christmas, my cousin offered me a head massager. Little did she know about its awesome physics I was about to unveil… and teach her! In fact, I got so amazed by this gift that I’ve decided to show it to many more people:

The Magic of Head Massagers

So, quickly, let me explain the thrilling physics of head massagers. When a long string is pulled then released, curiously, it makes all the long strings vibrate. However, short strings don’t.

It’s the same! Releasing a short string makes all the short strings vibrate, while long ones hardly move at all!

Exactly! Why???

Yes. But before getting to resonance, I need to talk about frequencies.

Frequency counts the number of repetitions of a motion in a given amount of time. In other words, the greater the frequency, the more often you’ll feel shakes. Now, crucially, a string, like in music instruments, has a certain natural frequency, which we usually call its pitch or musical note. And the same actually holds for all objects.

Yes! And, just like in music, these natural frequencies depend on the shapes of the strings and their materials. Therefore, all long strings have a same natural frequency, which differ from the common natural frequency of short strings. Now, when you release a long string, this long string will vibrate at its natural frequency. By resonance, this will excite all surrounding objects with the same natural frequency. This is why the vibrations of one long string will have all other long strings vibrating, and only them.

Terrifying Resonance

For me, what’s thrilling with head massagers is the universality of the phenomenon they unveil. Resonance is omnipresent! And it has some terrifying consequences.

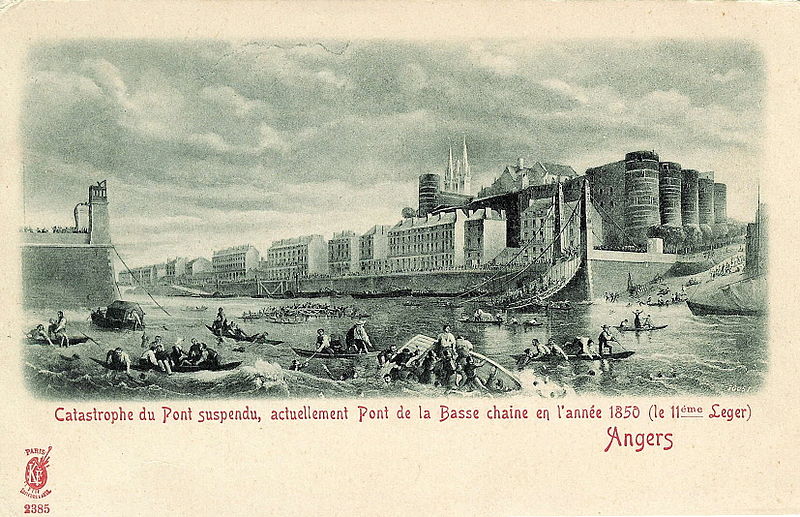

Exactly! They were referring to the collapse of the Angers bridge in 1850. This suspension bridge broke when a battalion of soldiers marched across it. While the attrition of the bridge and the bad weather of that day definitely played a role, it is believed that the resonance of their marching was what really triggered the collapse of the bridge. (Image from Wikimedia)

In fact, at that time, the phenomenon of resonance was already well known to military leaders, as they required battalions to break steps when crossing bridges. But this was evidently insufficient to prevent the Angers bridge from collapsing…

It’s not that easy. Every man-made construction has natural frequencies, and resonance with unforeseen vibrations may be impressively frightening. One particularly blatant example occurred for skyscrapers in Japan, slightly after a 9.0 earthquake:

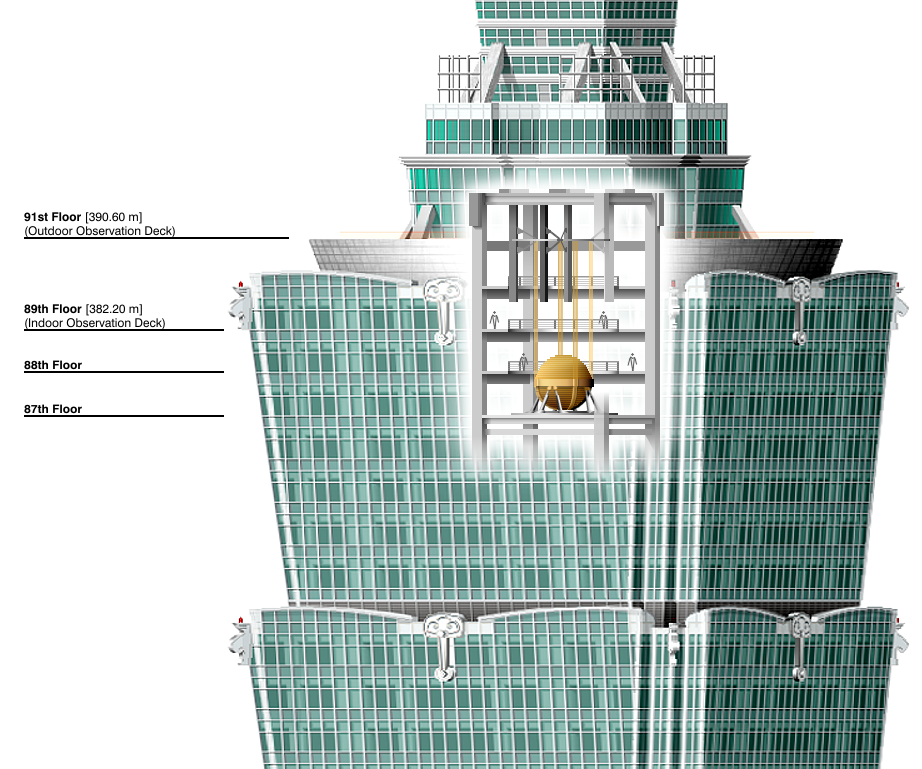

They have! Amusingly, the solution given to avoid oscillations of the previously-tallest-building-of-the-world Taipei 101 is to let some massive objects within the building oscillate without the building. More precisely, engineers put huge pendulums inside Taipei 101. These pendulums naturally capture the vibrations of the whole building.

A simplified way of looking at it is as follows. What matter in terms of vibrations are the oscillations of the center of mass. Given an earthquake, the whole building will have to vibrate. However, by allowing some of its mass to vibrate independently from the building itself, the vibrations of the actual building are decreased. Here’s a video of a simple experiment which displays this so-called mass damper phenomenon by comparing a first case without mass damper and a second with a mass damper:

Avoiding resonance, or, at least, diminishing its effects, is an important part of other civil engineering endeavors. Ship producers prevent resonance between waves and the ship, car manufacturers avoid noisy resonance between the engine and the body of the car and railway builders limit resonance between overhead lines. To come back with buildings before moving on to useful resonance, here’s a great more complete TedEds video:

Delightful Resonance

But resonance isn’t always a bad thing. For one thing, it enables spectacular shows with Tesla coils, as brilliantly explained in the following awesome video by the Gentleman Physicist:

Sorry… no. You can check a great explanation in this video by Drew Colpurs. Instead, I want to talk about even more essential applications of resonance.

Like radios. Have you ever thought about that? When you’re listening to 100 AM, you’re only hearing 100 AM. Doesn’t that blow your mind?

And this is thanks to resonance!

The key is the RLC circuit.

I don’t want to go to much into the details, but basically, a RLC circuit is made of 3 components: A resistance, an inductor and a capacitor. Crucially, this circuit has a natural frequency, which mainly depends on the inductor and the capacitor.

It means that if you inject electric current all at once in the RLC circuit, then the voltage at a point will oscillate at that natural frequency. But more importantly, if you inject an alternative electric current whose frequency is the same as the natural frequency of the RLC circuit, then, by resonance, the electric current within the RLC circuit will be hugely amplified.

Instead of a classical alternative current source, radios use the electromagnetic radio wave to trigger currents in their RLC circuits. And, crucially, by resonance, the current induced into the RLC circuit by electromagnetic radio waves is only that of the radio waves of the same frequency as the natural frequency of the RLC circuit! This is why, when we listen to 100 AM, we’re only hearing 100 AM. In fact, 100 AM stands for $100 \times 10^4$ hertz, which equals 1 MHz. This means that the 100 AM signal oscillates one million times per second.

We do! That’s because the 1 MHz signal is merely the carrier wave. To send an actual signal through the carrier wave, you need to modulate the carrier wave. This can be done by multiplying the carrier wave by the actual voice signal, which is of much lower frequency. This corresponds to the figure on the right, where the first curve, labelled “signal”, is the actual message to be sent.

If you’ve ever worked with sound signals, it definitely should! Just have a look at Google Image’s results for “Sound”.

Amazingly, yes. When you talk, you are basically modulating the pitch of your voice which acts like a wave carrier by multiplying this with the sound of words, which contains the actual message! Obviously, the slight difference with radio is that, instead of an electromagnetic wave, you’re using a mechanical wave of pressure of air.

Yes! Isn’t it amazing?

No. Let’s have a look inside our ears with this teaser of a BBC show:

Crucially, inside our ears, we have a collection of tiny hair cells of different heights, which are immersed in a fluid. These hair cells are precisely like the strings of our head massagers. They will only vibrate, if the fluid they are immersed in is vibrating at their natural frequency. Now, since this fluid is in contact with the air pressure right outside our ears, it vibrates accordingly to sound waves. So, amazingly, by detecting which hair cells are vibrating, our neuronal systems can distinguish the frequencies that make up the sound waves we are listening to! Isn’t it astonishing?

So really, head massagers are simply macroscopic replica of the awesome physical setting which is in place in our ears! That is mind-blowing! Now, I should mention that there are other applications of resonance in medicine. Most notably is the famous Magnetic Resonance Imagery (MRI) which enables to track brain activity. Another interesting application may be cancer treatment.

Music and Multiple Frequencies

Real sounds are actually additions of plenty of different frequencies. In fact, the surprising and yet fundamental result of Fourier analysis is the fact that all signals are compositions of different frequencies. But the same actually holds for natural frequencies.

I mean that objects actually have several natural frequencies. Granted, some are more “natural” than others, but the fact that they do have several of these frequencies is a phenomenon which is essential to music. As it turns out, the reason why several different musical pitches are called by the same name do strongly relies on that fact!

Yes! This is what’s beautiful pointed out by the amazing Marcus du Sautoy on the BBC show Story of Math:

Crucially, a string doesn’t only have one natural vibration mode. Granted, the main vibration mode corresponds to the string vibrating with only the two end points still. But, there are also vibrations with the middle point still, called the second mode. Or, with the first and second third points still, called the third mode. And so on… A beautiful visualization of that phenomenon has been set up by the great Brian Cox on this evening show by BBC:

The frequencies of the different vibration modes correspond to the natural frequencies of vibration of a string. Thus, when we excite a guitar string, it will vibrate at all the different vibration modes (although the first mode is the main one). Now, crucially, many of these vibration modes for a full string are common to the half string! In fact, all even vibration modes are vibration modes of half string. So, amazingly, the octave higher do contains all the vibrations of the octave lower do. That’s why they sound so harmonious!

That is precisely what I’m saying! When switching from one to the other, some of the hair cells of our ears still vibrate as they used to. And that’s why there’s this important harmony in our construction of music!

I know!

A Bit of Mathematics

Now, as a mathematician, I can’t leave you with the impression that resonance works because of some unexplained magic. So, in this last section, I will explain the universal underlying phenomenon. To do so, we’re going to need to generalize this pattern, which corresponds to doing mathematics.

First, we need to describe frequencies.

Frequency describes a repeating phenomenon, as it counts the number of times an initial state occurs in a unit of time. What would be the simplest mathematical structure which corresponds to that?

Something that comes back to its initial state… What does that sound like?

Exactly like a loop! In fact, let’s consider the simplest kind of loop: The circle! Looping on a circle is, I claim, the simplest setting in which the concept of frequency starts to make sense. So let’s imagine a point rotating anti-clockwisely (because, why not?) along a circle. The number of loops in one second then corresponds to the frequency of the vibration.

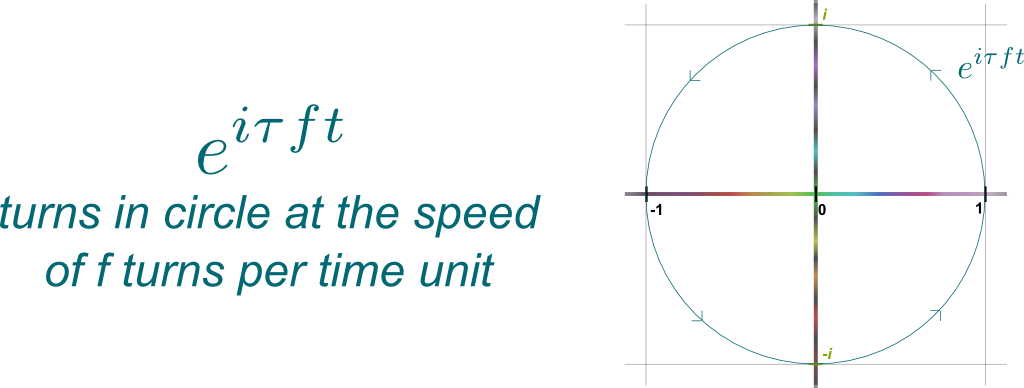

Precisely. Now, thanks to Euler’s beautiful identity, the motion of that point can be described by the trajectory $z(t) = e^{i\tau f t}$, where $\tau = 2\pi$ represents a turn, $f$ is the frequency of rotation and $t$ is time.

Yes! To calculate the frequency of the trajectory $z(t)$, we simply need to count how many times the car goes through the initial point 1 between times $t=0$ and $t=1$. Yet, the car goes through initial point 1 if and only if $f t$ is an integer $k$, in which case $z(t) = e^{i \tau f t} = e^{i \tau k} = 1$. Between times $t=0$ and $t=1$, this happens for integers $k$ between $f t= 0$ and $f t = f$. Thus, it happens $f$ times, meaning that there are $f$ oscillations within 1 unit of time. So, yes, $f$ is indeed the frequency.

Crucially, natural motions are induced by differential equations. So, if $f$ represents a natural frequency of an object, then $z(t)$ must be the solution to the physical law that the object must follow. This physical law is mathematically a differential equation, which is typically deduced from Newton’s or Maxwell’s laws. But, to be general, let’s not include any particular law, but, rather, we’ll deduce the physical law of the object merely from its natural frequency.

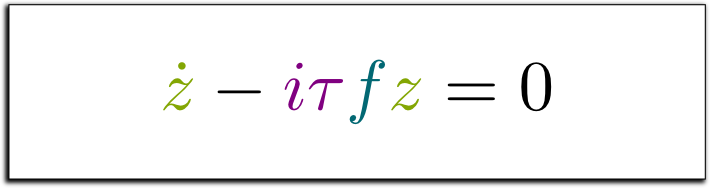

Sure! We know that $z$ is a solution to this physical law, so let’s search for the simplest differential equation it is a solution of. Now, denoting $\dot z$ the derivative of $z$, we have $\dot z = i \tau f e^{i \tau f t} = i \tau f z$. This shows that the physical law of the object must be $\dot z – i \tau f z = 0$. So, amazingly, we have characterized the fundamental differential equation of a physical object simply by knowing that it had a single natural frequency!

Now, let’s see what happens if an external source of energy was acting on our physical object. This corresponds to adding an oscillating action of the form $Z(t) = A e^{i \tau F t}$, where $A$ is the amplitude and $F$ the frequency of the external vibration. To see how this affects our physical object, we need to solve the equation $\dot z – i \tau f z = Z$.

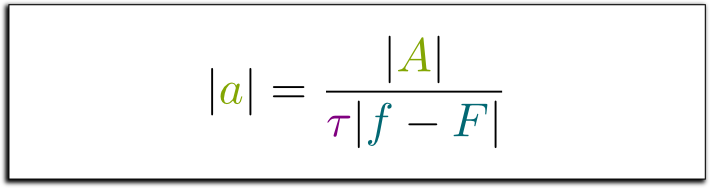

The solutions to such equations are vibrations at the frequency of the source. More precisely, they have the form $z(t) = a e^{i \tau F t}$. By plugging that into the equation, we obtain $i \tau F a e^{i \tau F t} – i \tau f a e^{i \tau F t} = A e^{i \tau F t}$. By dividing all by the oscillation term $e^{i \tau F t}$, we finally obtain the equation $i \tau a (F – f) = A$. In particular, the amplitude of vibration of the physical object has absolute value $|a|$ equal to:

This formula means that the amplitude of the car rotation is proportional to the amplitude $A$ of the external source, which is not much of a surprise. But, more importantly, it is inversely proportional to the difference of frequencies. So, astoundingly, if the frequency of the source perfectly matches that of our physical object, the amplitude of oscillations of our physical object is infinite! This is resonance at its extreme!

Yes, indeed! Now, in real life, it’s highly unlikely to have $F=f$. And, even if we have $F=f$, there are frictions which should prevent any blow up. To model these frictions, we should have noted that the circles don’t perfectly loop back to the initial point. Rather, they nearly get there, but the amplitude slightly decreases, yielding spirals rather than circles. A model of that is to use trajectories $z(t) = e^{-rt}e^{i \tau ft}$, whose fundamental differential equations are $\dot z + (r-i\tau f) z = 0$. Adding an external oscillating force $Z$ would then yield $a (i\tau F + r – i \tau f) = A$, and thus $a = A / (r+ i \tau (F-f))$. In particular, $|a| = |A|/\sqrt{r^2+\tau^2(F-f)^2}$, which never blows up if $r > 0$.

Conclusion

What’s fascinating with the resonance phenomenon is its omnipresence in the world around us. As Nikola Tesla put it, “if you want to understand the universe, think of energy, frequency and vibration“. In this universe of vibrations, resonance plays a central role.

I don’t think I am. Modern theories of physics like quantum mechanics are filled with waves. The concept of frequency is essential to these theories, and resonance is a highly counter-intuitive but key aspect to understand these theories. And the key to really understand waves lies in the mighty Fourier analysis. But before reading more about these, I suggest you pause another 3 minutes, to stare the amazing Chladni plate experiment by Brussup, which unveils some spectacular resonance phenomena appearing on a shaking plate:

The ‘minion’ chip in the brain explains everything you need to know about how the brain works. It’s also the biological clock and a nuclear fusion reactor. Minions inter-communicate by resonating. They have a huge memory capacity but limit our understanding to the equivalent of a piano with 103 octaves and explain personality. Know yourself and understand others.

Everything is very open with a precise clarification of the issues.

It was really informative. Your website is very useful. Thanks for sharing!