When you look at these pictures, what do you think about?

Each of these pictures is a symbol of peace, and it is likely that this word will pop up in your mind by looking at one of these pictures – at least.

Indeed. The symbol #1 was created in 1958 as a symbol for the nuclear disarmament campaign. The symbol is a combination of the semaphore signals for the letters “N” and “D,” standing for “nuclear disarmament”. It became a symbol for the anti-war movements. Symbol #2, the dove with an olive branch, is the Christian symbol of peace, as a reference to the story of Noah, and to Jesus’ baptism. Symbol #3 is the word “salaam” which means “peace” in Arabic. It has the same root as the Hebrew word “shalom”, which is another translation of “peace”. Symbol #4 is a picture of meditation practice. Meditation is a spiritual practice that is found in several religions around the world. It can be a supporting practice for inner peace. Symbol #5 became popular as a peace symbol in the 1960’s by American peace movements. Before, in 1940’s, it was the symbol of “victory” to celebrate the end of the Second World War.

Peace refers to a social state and to a psychological state depending on the context the word is being used. Conflict is usually perceived as antagonist to peace, which is more associated with tranquility. However, tranquility isn’t always peaceful, and you can also understand peace as a balance-seeking process.

Kind of, yes. In that case, it really depends on how well the person you are talking to will receive your anger and critique. If that person understands that critique and doesn’t lose their balance but recognize your emotion, then you will probably calm down and recover your inner peace. On the contrary, if that person refuses to hear you, or blames you and gets angry at you, then you are in for some aggressive relations until one of you decide to stop. I am sure you have experienced that before.

Now this also happens between social groups, organizations and countries. Think about revolutions and social movements.

That’s an example, yes. For centuries, black people in the U.S. did not have the same rights as white people. The political and social system as it was enforced inequalities, and created structural frustrations and dominations. Eventually, these became unbearable and the people decided it was time to change. They protested and started to refuse the domination, but the fight took many decades and many people died. In 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white passenger. She was arrested and became an icon of the movement for the civil rights and nonviolent civil disobedience. In 1964, the President of the United States signed into law the civil right act that ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, workplaces and facilities that served the general public.

You can also draw a parallel with several other revolutions and movements across history. Some never get recognition, either because they are too small or not strong enough. Some change the face of our societies. The revolutions in France, the US, in Russia, in China, in Egypt, in Chile, etc, are good examples. Usually the conflicts lead to changes in the balance of powers; sometimes they reinforce the power in place, sometimes the power shifts a little, or completely.

Yes, absolutely. Some conflicts between countries end with a peace treaty, some with an armistice, a surrender or a ceasefire. Some remain unsolved. In most cases, when we refer to “peace” between countries, it refers to the absence of an armed conflict with other countries.

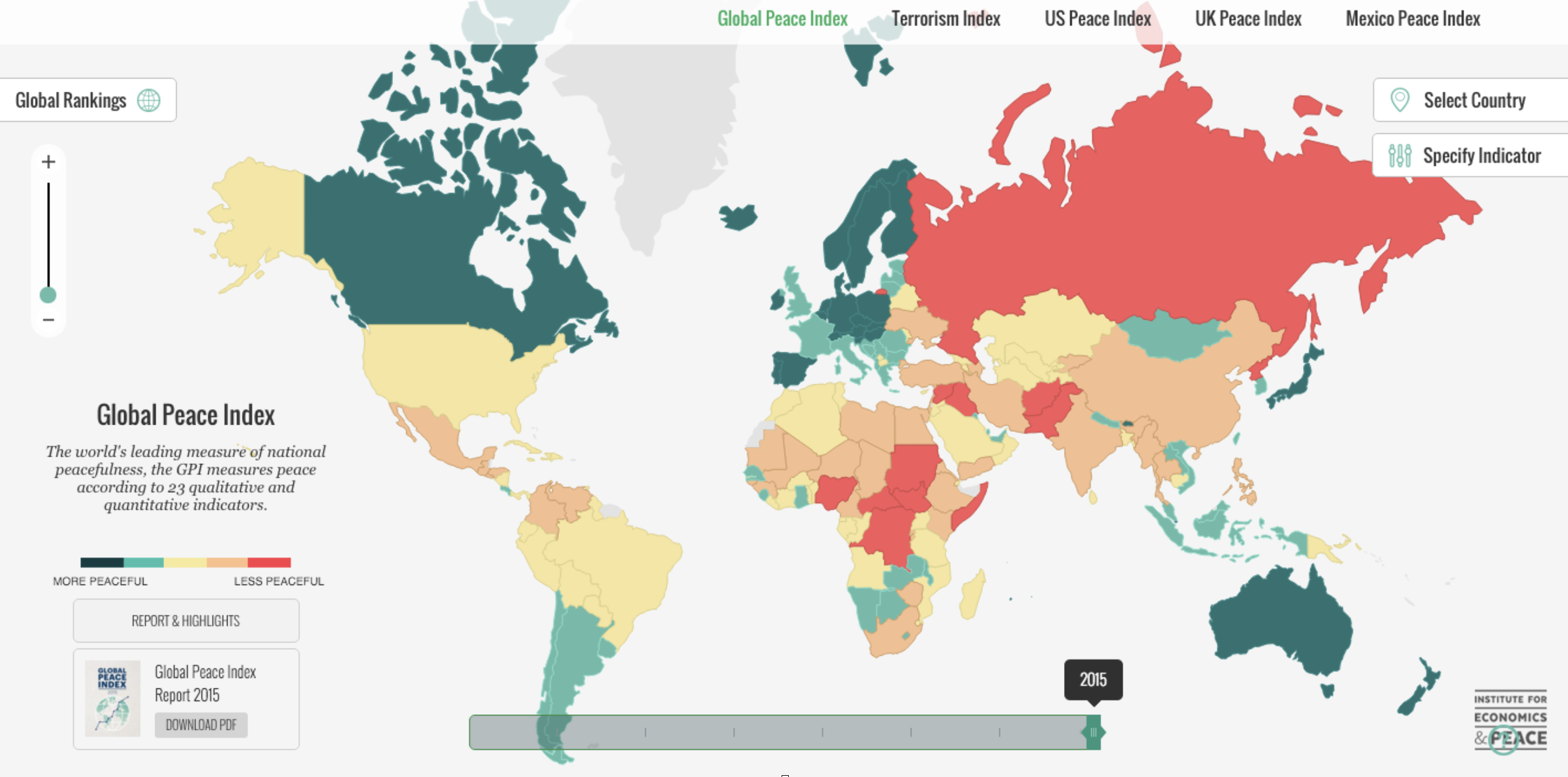

At least we can try! That’s what the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) does with the Global Peace Index (GPI). The GPI measures what the IEP calls “negative peace”: “the absence of violence or fear of violence”.

Before I go into statistical details, let me tell you why it matters to measure peace.

First, it makes it less abstract, sheds light on what we are talking about, and allows to measure peace. Even if this measure is far from being perfect, it creates a common ground to discuss and evaluate peacefulness.

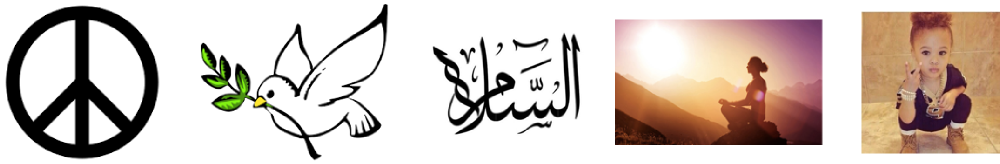

Second, the IEP uses the GPI to measure the economic value of peace and violence. In 2014, the economic impact of violence on the global economy was 14.3 trillion USD, which represents 13.4% of the cumulated world GDP. This number is obtained by using a violence containment model developed by IEP, and which includes 15 different variables such as global military expenditures, incarcerations, terrorism, small arms industry.

Third, measuring peace allows a better understanding of the attitudes, institutions and structures which allow to create a sustainably peaceful society and human potential to flourish. That is what the IEP calls “positive peace”, and it is measured by the PPI (Positive Peace Index). You can identify virtuous and vicious cycles of positive peace.

The GPI gauges “negative peace” in 163 countries using three broad themes:

- the extent of domestic and international conflicts,

- the level of social safety and security,

- the degree of militarization.

The Index was created in 2007, and it now uses 23 indicators to measure the level of countries’ domestic (internal peace indicator) and international (external peace indicator) conflicts.

| Dimensions | Indicator | Data Source | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ongoing Domestic and International Conflicts | 1 – Number and duration of internal conflicts | Uppsala conflict data program (UCDP) Battle-related deaths dataset | 2.56 |

| UCDP Non-State Conflict Dataset | |||

| UCDP One sided-violence Dataset | |||

| 2 – Number of deaths from organized conflict (external) | UCDP Armed Conflict Dataset | 5 | |

| 3 – Number of deaths from organized conflict (internal) | International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) Armed Conflict Database (ACD) | 5 | |

| 4 – Number, duration and role in external conflicts | Uppsala conflict data program (UCDP) Battle-related deaths dataset | 2.28 | |

| 5 – Intensity of organized internal conflict | Qualitative assessment by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) analysts | 5 | |

| 6 – Relations with neighboring countries | Qualitative assessment by the EIU analysts | 5 | |

| Social Safety and Security | 7 – Level of Perceived Criminality in Society | Qualitative assessment by the EIU analysts | 3 |

| 8 – Number of refugees and internally displaced people as percentage of the population | Office of the High Commissioner for refugees (UNHCR) mid-year trends | 4 | |

| Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) | |||

| 9 – Political Instability | Qualitative assessment by the EIU analysts | 4 | |

| 10 – Political Terror Scale | Qualitative assessment of Amnesty International | 4 | |

| US State Department yearly reports | |||

| 11 – Impact of terrorism | Institute for Economics and Peace (iEP) Global Terrorism Index (GTI) | 2 | |

| 12 – Number of homicides per 100,000 people | United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Surveys on Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Sustems (CTS) | 4 | |

| EIU estimates | |||

| 13 – Level of violent crime | Qualitative assessment by the EIU analysts | 4 | |

| 14 – Likelihood of violent demonstrations | Qualitative assessment by the EIU analysts | 3 | |

| 15 – Number of jailed population per 100,000 people | World Prison Biref International Centre for Prison Studies (ICPS) | 3 | |

| 16 – Number of internal security officers and police per 100,000 people | UNODC, EIU estimates | 3 | |

| Militarization | 17 – Military expenditures as a percentage of GDP | The military balance by International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) | 2 |

| 18 – The number of armed services personal per 100,000 people | The military balance by International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) | 2 | |

| 19 – Volume of transfers of major conventional weapons as recipient (import) per 100,000 people | Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) arms transfers database | 2 | |

| 20 – Volume of transfers of major conventional weapons as supplier (exports) per 100,000 people | Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) arms transfers database | 3 | |

| 21 – Financial contribution to UN peacekeeping missions | United Nations Committee on Contribution | 2 | |

| 22 – Nuclear and heavy weapons capabilities | The military balance by International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) | 3 | |

| Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) arms transfers database | |||

| UN Register of conventional arms | |||

| 23 – Ease of access to small arms and light weapons | Qualitative assessment by the EIU analysts | 3 |

No problem. You ask for a way to measure peace. When we measure something, we give it a number that makes sense within a given frame or scale. For instance, we can measure your size in meters, your weight in kg, your age in years, etc. To measure peace, we need first to create a scale of reference, something that will help to make sense of the number we can attribute to the state of peace.

Exactly. The GPI is a number between 1 and 5, with 5 being the least peaceful. This number is computed based on a series of indicators, which are themselves given a score between 1 and 5. In case the indicator is qualitative, the analysts use a scoring criteria scale is used. In case the indicator is quantitative, they use scoring bands.

For instance, “23 – Ease of access to small arms and light weapons” is a qualitative indicator. The Economist Intelligence Unit Analysts scored each country with the help of the following scoring criteria:

- 1 = Very limited access: The country has developed policy instruments and best practices, such as firearm licenses, strengthening of export controls, codes of conduct, firearms or ammunition marking.

- 2 = Limited access: The regulation implies that it is difficult, time-consuming and costly to obtain firearms; domestic firearms regulation also reduces the ease with which legal arms are diverted to illicit markets.

- 3 = Moderate access: There are regulations and commitment to ensure controls on civilian possession of firearms, although inadequate controls are not sufficient to stem the flow of illegal weapons.

- 4 = Easy access: There are basic regulations, but they are not effectively enforced; obtaining firearms is straightforward.

- 5 = Very easy access: There is no regulation of civilian possession, ownership, storage, carriage and use of firearms.

“3 – Number of death from organized conflict (internal)” is a quantitative indicator, and a scoring band was used:

- 1 = 0 to 23 deaths,

- 2 = 24 to 998 deaths,

- 3 = 999 to 4,998 deaths,

- 4 = 4,999 to 9,998 deaths,

- 5 = > 9,999 deaths

Each of the indicator has a weight, that determines how important the indicator is for the overall GPI. The higher the weight, the more the score of the indicator will make a difference for the GPI of a given country. For instance, the number of death from organized conflict (internal) has a weight of 5: the maximum. It means that a country’s score in this category will have a higher impact on the total GPI of that country, than the GDP percentage that goes towards military expenditures (weight 2)

Also, internal peace dimensions weight for 60% of the GPI, and external dimensions for 40% following a debate between the members of the advisory panel for the overall composite score. The argument was that a higher level of internal peace was more likely to lead to or correlate with a higher level of external peace.

Look at the numbers cloud! It shows which indicator has the most significant weight in the GPI formula. Try to look for the indicator number in the table, and see how big it appears in the graph!

Look at the numbers cloud! It shows which indicator has the most significant weight in the GPI formula. Try to look for the indicator number in the table, and see how big it appears in the graph!

Well, it’s not! So when the data are not available, estimations are used instead. That is one among other limits of the index. That is work in progress. Each year, the GPI is being released in London, Washington DC and at the UN Secretariat in New York.

The index development was inspired by Steve Killelea, founder of the IEP. It has been endorsed by Kofi Annan, the Dalai Lama, Desmond Tutu, Muhammad Yunus, Jeffrey Sachs, Jan Eliasson and Jimmy Carter. Check out the website of Vision of Humanity and find out the GPI and the value of the indicators for each country in 2O15.